This is Just To Say

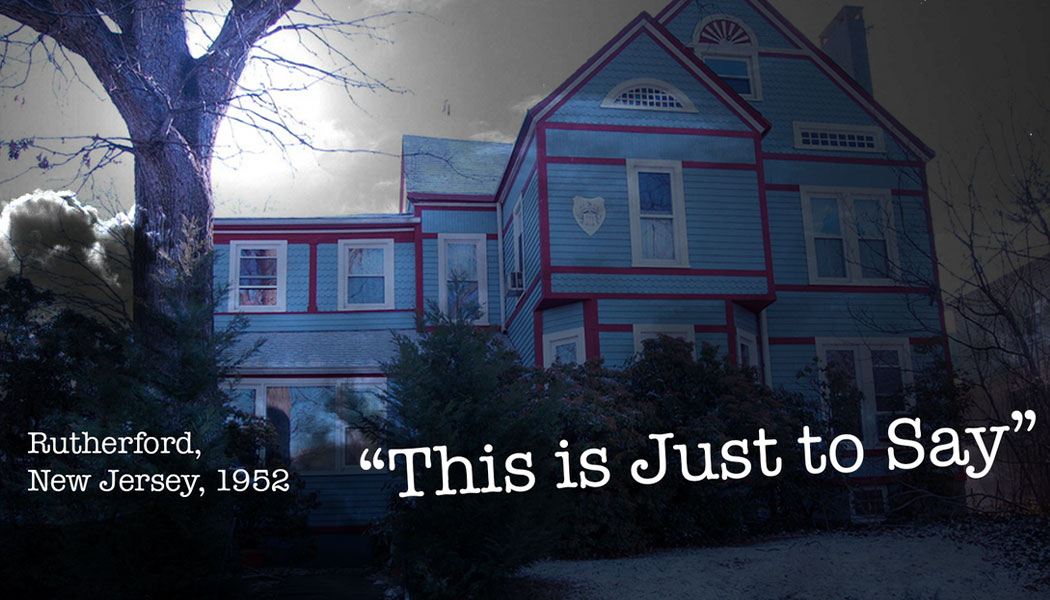

I’m hiding in a bush outside a house in Rutherford, New Jersey, on the evening of March 11th, 1952. It's cold. The wind is swiping the siding behind me and moving the dirt beneath me. Wooden slats breathe and shift against each other like the scales of a snake.

Tucked between my rib and my armpit is a book, wrapped in a bag.

The bush I’m in is a fir. Brambles the texture of barbed wire are wreathed around my neck. It isn’t the worst I’ve had to go through for work, but it’s close.

I'm waiting for a man named Ginsberg to open the front door, yell back inside some kind of goodbye, walk to his car and drive away.

That's when I'll complete my delivery.

Ginsberg will write about tonight in a diary entry. He’ll date it March 11, 1952. This is the house, owned by a Mr. Williams. There are cars parked on the street. There isn't much going on inside the house at the moment, if anything. I'm starting to think it may be empty. So far the only observable moments of interest have been around the rest of the neighborhood.

Across the street, six minutes ago, a garage door opened and a woman stood there, rearranging items on a shelf.

She looks out the open door, squinting into the light and at once I have the feeling, the certainty, that she can see me, that she’s making eye contact with me. But I know that isn’t possible. I'm wearing a fully—integrated lightsuit, local proximity cloaking enabled.

Five and three quarters minutes ago, a man drove a car into the driveway and parked in the garage. He got out he gave the woman a kiss on the cheek, and the garage door closed.

They don't see me.

I'm wondering if the date in the book was written down the same night or made up by Ginsberg ex post facto, which might mean I’m at the wrong date altogether.

There's always a chance. History is like that sometimes, in my experience. My own memory for dates and locations after the fact isn't good at all, approximations are the best I can do.

A young boy on roller skates goes by, pulled by a dog, a golden retriever. I'm impressed, because it's dark, and because roller skates are impossible to use.

Nobody from my time can use them.

From behind me, I hear the voices of two men nearing the front of the house. One of them opens the door, steps out, turns back, and says into the opening, "and I'll say hi to Jack for you."

“Yes, that would be nice. He's always somewhere,” comes the reply from Williams inside. The door shuts again.

The man leaving, who I’m assuming must be Ginsberg, shuffles down the walk to his car, gets in, fumbles around for thirty seconds, starts the car and drives off.

I wait another minute or two, and now it's time for me to deliver my package.

In 1952, doorbells are the norm, but one doesn’t seem to be installed in this house. Meaning I have to knock, in a way natural to people of the period. This makes me nervous. My therapist says it’s neurosociotemporal anxiety, common in this line of work. I am a nervous system out of time attempting to interact with other nervous systems in time.

My anxiety is compounded because this delivery is different.

In order to knock on the door, I would normally have to strictly adhere to temporal normality rules. I'd have to go behind the house, hop over the fence, go through the neighbor's yard to the next street, walk a distance down, find a safe place to extinguish my proximity cloak, change into an appropriate outfit and walk the block and a half back to the recipient’s door.

I won't be doing any of that this time.

This is my first “high profile” delivery. This one, the sender doesn't want anything observed—nothing on record. I'm to engage in what's called 'stealth protocol yellow'.

I take some deep breaths. I’m ready.

I come out of the bush and go up the steps. I knock on the door. When Williams opens it, I won't be standing there, not to an eye as-yet untrained by decades upon decades of game graphics, multidimensional films, and mixed reality implants.

This is what happens. He opens the door. He looks out into the night. He sees nobody, but of course I’m standing there.

I step forward, through the opening and into the man, pushing him aside. He stumbles back but steadies himself.

“William Williams?”

I shut the door behind me. The man cowers, clutching his chest. He gasps, he hisses.

“Devilry!”

I extinguish my proximity cloak and stand before him, unassuming but for my uniform and a protective stance.

“It's not devilry, it's delivery,” I say. “I’m a delivery guy from the future. I think that's the correct terminology. Maybe it’s delivery chap?”

“The future?” Williams gulps like a fish.

“Yeah, the future. Pretend it's a company you’ve never heard of if that makes it easier to think about.”

From his coiled energy I can see Williams is still deciding whether to attempt to rush me. I know he won’t, not because I’m from the future, but because he’s a poet.

He says nothing.

I clear my throat.

“What am I delivering, you might ask? Mr. Williams?”

“What? Yes. Uh, what are you delivering? Wait, no, you're in my house—you shouldn't be here! I don't care how...how invisible you are sometimes.”

“Hidden is a better way to describe it. But now I’m not hidden. You are the only entity at this cross-section authorized to see me. That’s some small print.”

“Well then,” Williams said, considering, “I’ll push you out the front door again and you'll have to hide.”

“I couldn't allow you to remove me from the premises. Would you like to know what I'm delivering?”

Williams stands there looking at me.

"Well," he eventually says, flinging his hands at me. "Get on with it."

I pull out the book, and hand it to him still wrapped. He's got to open it, that’s one of the conditions.

“It's a book,” I say.

“Okay? It's a book from the future, and you want me to open it? Why does that strike me as wrong? Unsafe somehow. Not that I believe any of this.”

“Everybody asks that. Not to worry, there's nothing about this delivery that will change history in any substantive way. It's a job, and while I can't cosign the intent of the delivery or vouch for its contents, what I can do is deliver it. I've only to make note of your reaction, and I'll be on my way.”

“What do you mean, make note of my reaction?”

I gesture at the book.

“Nobody reads these anymore. But a lot of people have read this one.”

“Look, if you broke in here to give me a bible…”

“It’s not a bible. It’s something else, specifically meant for you. You're to open it and see what it says. Flip through. React to what you see."

Williams begins to unwrap the book. He tears the top right and top left, then pulls the book from the casing. It's bright red, leather-bound and in the center, stamped in gold plated letters, are the words "This is Just To Say."

"I..." He doesn’t finish the sentence. I can see the gears in his head turning. I can see him reaching into his guts for the fortitude to get through this moment, knowing something is profoundly wrong.

"Open it."

"Yes, of course."

I record all of this, I can't help but do it. My lightsuit automatically records everything with four-dimensional reconstructive fidelity. The sender will be able to relive this moment, once or as many times as he wants, from any angle, any perspective.

The book is open, the flustered Williams is flipping through the pages. Slowly at first, then faster and faster. Finally he looks up at me, his face the color of a tomato, drops of sweat appearing on his temples and on his neck. He's trembling, he’s having a hard time standing straight up.

I hope his reaction is sufficient for the sender.

“This poem isn't even published!” Williams says. “I wrote this twenty years ago!"

“It's published in a decade or so," I tell him. "Your friends, I think one just left, your friends convince you. It becomes the most well-known poem, even if...the format..."

He's not listening to me. He's staring at the book. Still flipping.

“What kind of abomination—is this a joke? Is this how you in the future deal with dead writers? Turn their words into... I can't even classify this. What simpleton thinks this derivative...thinks this parody, no, this perversion is worthy of fruition? Who wrote this?"

"A lot of people will write it. In the 21st century, your poem is one of the more participatory instances of something called a 'meme’, which means a virally transmitted idea. The man who coins the term is a child at this time, and the technology along which these ideas travel hasn't been thought of yet.”

My lightsuit tightens around my throat, preventing me from saying more. It’s for protection, to keep reality in check - suppose I mention the boy’s name and this poet goes off in search of him? However unlikely that eventuality, stealth code yellow.

“When you say a lot of people, how many is that?”

“Almost everyone at some point seems to write a version of this poem. Millions of people. Millions of poems more than could fit in a book.“

I see him trying to climb this mental hill, try to see if it is something he can manage. It doesn't last. His shoulders slump, his eyes scan the floor.

“What of the rest of it? My novels? The collections? My career as a doctor? Do they know any of it?”

“The plums in the icebox poem, and parodies of it. That’s how you survive in the social consciousness. I don't think people are aware you were a doctor. I wasn’t.”

This uncovering, this revelation—it seems to destroy him. Rips into him, invalidates him. I watch an ego wrapped in a nervous system shrivel up like a salted slug. Whatever multidimensional man this had been was now wholly reduced—by a book of jokes.

The future has reached back to laugh at William Carlos Williams.

“I have delivered the poems that were in the future,” I say, “and which you are probably wishing were never written.”

I don't want to say any of this, but the sender paid for it as a delivery condition.

“Forgive me, it was delicious. So sweet and so cold.”

Now I’m leaving.

I’m leaving now.

I open my eyes. I'm back in the sender’s time, in Rutherford, New Jersey.

I’m waiting for my body to stop buzzing, for my lightsuit to finish pulling all of the strands of me back together.

I start a call. The sender answers, standing before me, looking impatient.

“You got it?”

He means payment for the delivery. It's already in my account, I can read the notifications - down and to the right of my vision. I swipe them away.

"Funds received.”

"Good. Video’s transferring?"

"Transfer initiated."

A moment goes by before he has it, the seed from which to reconstruct everything I’ve just experienced.

“Thank you again,” I say, “For using Jack of All Times Courier Services.”

The sender nods, already forgetting I’m there. He ends the call. I’m alone.

It's abrupt, and his callous informality bothers me. I want to call back and say “This was wrong. We were wrong for this.”

I want to make him feel the same way the poet felt, small, insignificant, a footnote in time, a joke.

Of course I don’t turn around, I don’t go back. I have another delivery, another client.

I’m a Jack.

It’s how I survive.